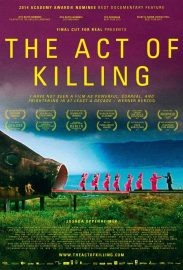

https://www.filmplatform.net/product/the-act-of-killing-2

In a country where killers are celebrated as heroes, the filmmakers challenge unrepentant death squad leader Anwar Congo and his friends to dramatise their role in genocide. But their idea of being in a movie is not to provide testimony for a documentary: they want to be stars in their favourite film genres—gangster, western, musical. They write the scripts. They play themselves. And they play their victims. This is a cinematic fever dream, an unsettling journey deep into the imaginations of mass-murderers and the shockingly banal regime of corruption and impunity they inhabit.

“If we are to transform Indonesia into the democracy it claims to be, citizens must recognize the terror and repression on which our contemporary history has been built. No film, or any other work of art for that matter, has done this more effectively than THE ACT OF KILLING. [It] is essential viewing for us all.”

“An absolute and unique masterpiece.”

“An extraordinary portrayal of genocide. To the inevitable question: what were they thinking, Joshua Oppenheimer provides an answer. It starts as a dreamscape, an attempt to allow the perpetrators to reenact what they did, and then something truly amazing happens. The dream dissolves into nightmare and then into bitter reality. An amazing and impressive film.”

“I have not seen a film as powerful, surreal, and frightening in at least a decade.”