https://www.filmplatform.net/product/black-wave

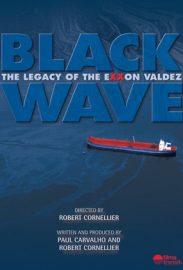

In the early hours of March 24th 1989 the Exxon Valdez oil supertanker runs aground in Alaska. It discharges millions of gallons of crude oil. The incident becomes the biggest environmental catastrophe in North American history. For twenty years, Riki Ott and the fishermen of the little town of Cordova, Alaska have waged the longest legal battle in U.S. history against the world’s most powerful oil company – ExxonMobil. They tell us all about the environmental, social and economic consequences of the black wave that changed their lives forever. This is the legacy of the Exxon Valdez.

When the Exxon Valdez ran aground in 1989, Andrew Wills was a successful herring fisherman in Alaska and the owner of three canneries.

The 11 million gallons of crude oil from the tanker destroyed the herring population and Wills’s fishing career, so he borrowed money to open a bookshop, a café and the Mermaid Bed and Breakfast in Homer, Alaska.

Wills had expected to use his $85,000 share of the $2.5 billion punitive damage settlement against Exxon to pay off some of his debts. The U.S. Supreme Court decision on Wednesday that cuts the damages to about $500 million means that Wills will receive only $15,000, he said. “After everything we’ve been through, that’s barely enough to cover payroll for a month,” he said. “This is a knife in the gut.”

Across Alaska, plaintiffs in the long-running lawsuit against Exxon reacted to the decision with sorrow and rage, numbed only by relief that their legal saga is finally over. “This decision is a giant cold slap in the face,” said Garland Blanchard, 59, a third generation fisherman who said he had lost his marriage along with his two fishing boats, house, cat and dog to financial pressures caused by the spill. Blanchard expects to receive less than $100,000 from the settlement, down from the $1.2 million he had previously expected. “Our lives and businesses have been destroyed and we get basically nothing,” he said. “It’s pathetic.”

Local radio stations were just breaking news of the decision as Alicia Jensen opened the Killer Whale Café in Cordova, Alaska, on Wednesday morning. Just as it has nearly every day for two decades, the spill and the legal case dominated the customers’ conversations. “This has been the primary focus of this town for most of my life,” said Jensen, 33, who owns the café. “I’m glad that it’s over, and everybody can get on with our lives.”

The city of Homer was prepared to place the $4 million to $5 million it was to receive in an endowment to help pay for social services, said Walt Wrede, the city manager. Now the city will receive a fraction of that amount. “This is a very depressing verdict,” Wrede said, “and people here are just really disappointed.”