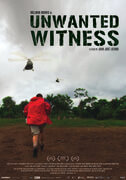

https://www.filmplatform.net/product/unwanted-witness-22

Hollman Morris is an internationally acclaimed journalist whose weekly television show, Contravía, boldly confronts the violence that ravages his homeland of Colombia. Though he has won prestigious awards abroad, at home he is faced with death threats and intimidation, and this puts a strain on his family life.

Hollman Morris, 39 years old, Colombian journalist.

For 15 years Morris has covered the internal conflict in Colombia, paying particular attention to the theme of human rights. Since 2002 he has produced and directed the television show Contravia “countercurrent”. Through dozens of half-hour shows, Hollman Morris has filmed eyewitness accounts of the most serious human rights situations in Colombia, constituting one of the most important video archives of the country’s recent history. The show has been supported by the European Union, the Open Society Institute and the governments of Canada, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands.

In November 2007 he received one of the world’s most prestigious prizes: the Human Rights Watch Defender Award.

Colombia: under the specter of self-censorship

According to ‘Reporters without Borders’, Colombia remains one of the most dangerous countries for journalists. Even though the frequency of kidnapping and murder has diminished during the last three years, the pressure exerted on journalists by hidden forces (guerilla, paramilitary, drug traffickers, politicians and corrupt government officials) remains overbearing. In many regions of the country that remain controlled by the interests of a select few, the most aberrant attempts against human dignity occur in the midst of a conniving silence. Journalists and their employers prefer to keep quiet or change the subject, justifying themselves by saying: in this country many people who have spoken out have died, and the justice system doesn’t work anyway. The assassins occupy powerful positions and people are tired of it all, they just want a break.

This environment of self-censorship along with the significant economical crisis at the end of the 90’s considerably reduced the freedom of the press in Colombia. In 1999, out of the three nationwide newspapers, only one survives today and is owned by the families of the Vice-President and the Defense Minister. This newspaper is written by journalists based in Bogota, far from the conflict zones. Articles covering the conflict’s impact on civilians are usually taken straight from the Defense Ministry’s official press releases. The language used in these official releases directly reflects the sitting government’s security policy: for example, the expression internal conflict is replaced by terrorist threat, an interpretation that ignores more than four million internal refugees and insists on speaking of a terrorist threat instead of internal armed conflict.

It is only fair to mention that the journalists most critical of the régime and those who denounce the humanitarian crisis lived by civilians or those who venture to seriously analyze the situation do give their opinion in this newspaper, but only in the little-read editorial pages. And only 200’000 copies are printed in a country of 28 million adults!

A distant war

The last few years have brought enormous changes to the world of televised news: documentaries covering the internal conflict that involve travel outside of Bogota and filming in the field have completely disappeared (with the exception of CONTRAVIA of course). Today two of the three national television channels have opinion shows, interviews and debates which sometimes discuss the war in Colombia, but from afar, without showing images from the field. The effect of these aseptic debates on the public is to make them think that the war is far away, and that in the end, it is not so bad. Because even if the subject of debate remains macabre – such as the massacre of a whole village – the images that reach the public are neutral: well-dressed, educated people sitting around a table in a television studio, with a nighttime city view as a backdrop.

In the end, the news shows argued that the public was tired of seeing corpses and that positive aspects of the country must be discussed. Thus 70% of every show is dedicated to covering sports, local show-biz and catchy anecdotes about national policy.

CONTRAVIA, the show

It is in this absence of images of the ‘other Colombia’ (that of the war and its victims), that CONTRAVIA was created. For the first time indigenous peoples, Afro-colombians, organized farmers, community leaders and victims of war crimes were given an opportunity to voice their opinions on television. Their lives and stories finally reached the public. But this ‘other reality’ is not good publicity for the country, and the lead journalist started receiving threats, mainly after certain episodes led to the reopening of criminal investigations against army officers or government employees implicated in human rights violations. The journalist’s communications were tapped by police authorities; the show was suspended, then shifted to a less favorable time slot. After the journalist received threats against his family the show was once again suspended; consequently he briefly moved abroad and the show was eventually put on the air again but at an even less favorable time than before. Several international awards followed, meaning bad publicity for the country, even more persistent threats, a newly elected government hostile to criticism, the EU’s disengagement from programs promoting democracy and peace in Colombia, and, finally, the possible end of the show.

After receiving the 2006 Canadian Journalists for Free Expression “International Press Freedom Award”, Hollman declared: “Seen in an international context, Colombia represents one of those grey zones for which there appears no solution. One of those endless conflicts that fails to interest either the media or public authorities and is eventually forgotten. For us journalists coming out of these grey zones, we know to what point our words can save lives, and it is not only about the life and death of our compatriots, but also about the life and death of Humanity in short. As said by Anna Politkovskaïa: ‘It’s about all of us’.”